This week, the United Nations sent out its annual appeal for funds for 2026, but sought only $33 billion – half of what it needs to help billions of people facing war, poverty and climate disasters globally.

The message could not have been more telling.

But the warning signs were already there. In 2025, the global humanitarian system was forced to confront a brutal reality: money is running out. Major institutional donors across Europe and North America slashed aid budgets and diverted funding to domestic priorities and security spending.

Flagship UN projects were left chronically underfunded, and NGOs like Save the Children were forced to discontinue programmes just as conflict, displacement, and climate disasters pushed needs to historic highs.

With an immediate 25 percent drop in revenue, our staff all over the world had to give children in our schools, clinics and child protection programmes the heartbreaking news that we would not be able to continue. With great effort and risk to our own solvency, we were able to keep the most acute life-saving programmes running, barely.

We’ve been talking about the role of the private sector in humanitarian response for decades, but now, after a severe 2025, we can’t keep pretending that public and philanthropic funding alone can sustain the world’s humanitarian response.

The scale of need has outgrown the architecture on which it was built. At the end of a year when many UN Agencies and NGOs have faced double-digit funding reductions, the role of the private sector is no longer optional but essential.

For we know that if we want to reach people faster and more effectively, we need the private sector not as a side partner, but as a core part of the solution. The private sector brings real value, not just resources, but different ways of thinking at a time when an increasingly unstable world is a threat to all our mandates and ambitions.

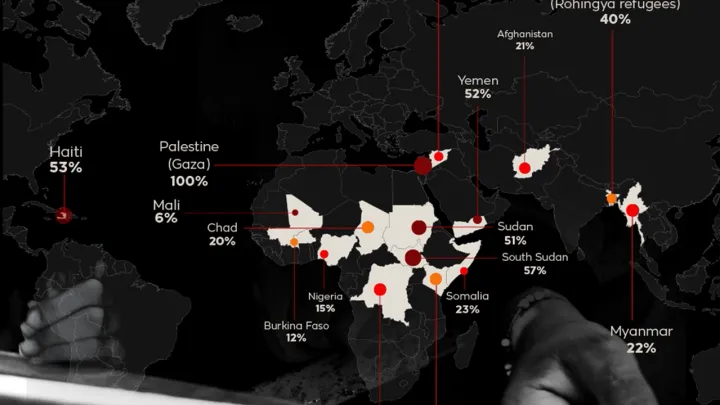

The impact of this increasing instability on children is unacceptable - and heartbreaking. One in every five children lives in active conflict zones where they are being killed, maimed, sexually assaulted and abducted in record numbers, according to a new report by Save the Children.

The number of children displaced globally is around 50 million. About 1.12 billion children globally — almost half of the world’s children — are unable to afford a balanced diet, and millions go hungry daily.

The private sector already shapes humanitarian outcomes through logistics, data systems, energy infrastructure, communications networks, and through the markets that people rely on for basic goods. Technology companies, accelerated by AI, are having a huge impact on people’s lives and how they access education, entertainment, identity, safety, our politics and, increasingly, global stability.

While corporate responsibility has existed for decades, what distinguishes today’s moment is the unprecedented scale and integration of private-sector capabilities into core humanitarian operations, alongside new financial instruments—blended finance, impact investment, parametric insurance—that extend beyond traditional charitable giving. These approaches offer both capital and operational innovations that weren’t widely deployed in humanitarian settings before.

Populations in crisis desperately need the private sector to step in.

Many years ago, one of Kenya’s leading telecom providers agreed to offer free Wi-Fi for schools in Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. For that, they had to build a tower, which, within a year, became a major income generator.

They hadn’t seen refugees as consumers or entrepreneurs – economic players with agency and disposable income – and maybe that is partly due to how we, as aid organisations, have for a long time portrayed people in need.

The private sector brings value that goes far beyond money. It brings innovation, efficiency, and a willingness to challenge outdated systems. Private companies are driving digitalisation, data analytics, AI and supply chain models that can radically increase reach and efficiency.

Partnerships that work

During the early stages of the Ukraine crisis, our partnership with one of the world’s leading e-commerce companies combined its supply chain and technology excellence with our experience in reaching vulnerable people.

By aligning, we unlocked an entirely new level of collaboration. The ability to leverage their existing warehousing infrastructure and network of suppliers enabled us to reach communities in record time.

The partnership stands as a blueprint for how companies can use their strengths to help solve seemingly intractable humanitarian challenges.

In a year when traditional humanitarian financing is collapsing, new forms of financing are not optional extras but critical to help us towards real, long-term resilience.

Save the Children Global Ventures combines investment expertise with our organisation’s experience over more than 100 years on how to deliver impact in challenging environments.

We invest in social enterprises and technologies that are aimed at scaling solutions for children. This way, we generate an income stream and solutions that we can use and scale in our own programmes.

But these partnerships are not without risk.

Some companies might attempt to offset exploitative practices—such as child labour or environmentally harmful operations—through charitable donations or humanitarian partnerships, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as reputation laundering.

Partnerships must ensure that businesses’ core practices align with humanitarian principles, or else risk causing harm while claiming impact.

When operating in politically contested or militarised environments, the line between humanitarian action and military or political strategic interests can blur very quickly if not guarded carefully, and damage trust sometimes irreparably.

The Gaza Humanitarian Foundation is a grotesque example of this, in which private sector contractors allowed aid to be instrumentalised for military objectives. No questions asked, no principles applied.

At Save the Children, we have a long history of public-private engagement, and we have learned that when roles are clear- when businesses bring innovation and scale, and humanitarian actors bring legitimacy, local trust, and humanitarian principles of engagement – the results can be extraordinary. But when motives or mandates blur, consequences can be costly.

So the question isn’t whether the private sector belongs in humanitarian work, it’s how we govern that relationship. It’s how we design partnerships that are transparent, accountable, and grounded in humanitarian principles, so that market logic strengthens rather than distorts our mission. Resilient markets and resilient communities depend on each other.

In a world where traditional aid is shrinking and needs are exploding, the private sector’s engagement is no longer a nice-to-have. It’s the only way to keep the humanitarian system alive and support the children who need it most.