When Joe Biden was elected president in November last year, his success was greeted with much fanfare in one corner of southeast Europe. In Bosnia and Kosovo, the election of the former senator not only seemed to augur hope but also raised expectations that America would be 'back'.

Perhaps in no other part of Europe was there a sense that one of their own had assumed the most consequential political office. In fact, prior to and after the November elections, analysts in Bosnia raced to outdo each other in predicting how significant this country was for the new president and how quickly he would get involved in resolving the political stalemate.

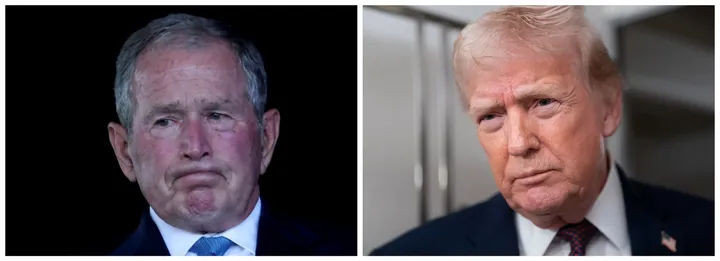

The euphoria and the inflated expectations sprang from Biden's advocacy for Bosniaks and Kosovar Albanians in the 1990s. When Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic launched his wars of conquest three decades ago, the George H. W. Bush and then the Bill Clinton administrations dithered and failed to confront aggression decisively at the outset.

However, a number of leading American legislators took up the cause of Bosnia and provided persistent support for the Bosniaks on Capitol Hill. Senator Biden was one of the most vocal supporters of Bosnia's right to self-defense amid the onslaught. In fact, the senator who had overcome a speech impediment in his youth is now remembered for his eloquent speeches supportive of Bosnia. Biden similarly came to the defense of Kosovar Albanians throughout the 1990s.

Biden's advocacy for Bosnia and Kosovo three decades ago had raised expectations over the last several months that the new president will be involved in the Balkans again. Much has changed over the past thirty years and new domestic and foreign priorities are on the agenda. The euphoria and the inflated hopes have by now largely subsided and a new sense of realism is sinking in.

In early March, the White House released its Interim National Security Strategic Guidance which reaffirms the Administration's commitment to the transatlantic alliance. NATO enlargement and the Balkans are noticeably absent from this strategic document.

In fact, the focus is on countering the rise of China and ending the “forever wars.” As Biden's first-hundred-days-in office benchmark approached, the president announced an American troop withdrawal from Afghanistan by September this year.

So where, realistically, is the Balkans in Biden's foreign policy?

While not a priority, the Balkans is a region where the US has invested politically, militarily and financially since the 1990s. Despite the considerable investment, the region is still in limbo, with a receding perspective of European Union membership.

China and Russia have been making inroads in recent years as the US shifted its attention elsewhere. If the peace - and American investment in Bosnia and Kosovo - are not secured, the Balkans risk remaining a volatile part of this corner of Europe.

The Balkans offer the Biden Administration an opportunity to both secure American investment and score a quick foreign policy success. Unlike American military involvement in the Middle East, the Balkans remains a region where US intervention was a success. In fact, there is virtually no anti-American sentiment among Bosniaks and Kosovars. This stands in sharp contrast with much of the rest of Europe.

To move the region forward, the Biden Administration should push for NATO enlargement to include Bosnia and Kosovo. The majority in Bosnia – primarily Bosniaks Muslims and Croat Catholics - are still in favour of joining NATO but this majority is slipping.

Bosnian Serb leaders in the political entity known as Republika Srpska are now increasingly opposed to the country's accession to NATO. This was not the case a decade ago and is indicative of how quickly support for the pro-Western course can dissipate.

With a new government in place, Kosovo is set to continue on its pro-American and pro-Western course. The newest state in Europe should not be held back simply because full normalisation with Serbia is taking time.

Ensuring that Kosovo has a clear roadmap to full NATO membership in the near future will serve to maintain stability in the Balkans. With EU membership for Kosovo a distant ideal, a clear path to NATO becomes all the more important. Serbia's decision to opt out of the NATO integration process for now should have no bearing on the rest of the region.

The opportunity for the Biden Administration to consolidate the Balkans firmly within the Atlantic Alliance will present itself at the NATO Summit in June. If Biden were to fast-track Bosnia's and Kosovo's accession to NATO, this would give both countries a sense of a brighter future and help anchor the two states firmly on a pro-Western course. The American political, military and economic investment in Bosnia and Kosovo over the past two decades would be secured.

After all, strategic imperatives should override any bureaucratic concerns over whether sufficient reforms have been implemented. The history of NATO enlargement is a history of how the Alliance prioritised strategic decisions over concerns about domestic politics. Greece was admitted in 1952 shortly after the Greek Civil War. West Germany became a NATO member in 1955 while remaining under American tutelage. Spain joined the Alliance in 1982 not long after the dictatorship.

A similar approach of admitting new members and then supporting their democratic development within NATO should be applied to the Balkans. Unlike previous NATO enlargement, the accession of two relatively small states of Bosnia and Kosovo would be very cost-effective. This foreign policy success is within easy reach and would be a lasting legacy for President Biden.