In 1896, a new entertainment district on the shores of a man-made lake by Lagymanyos in Budapest was opened to the public.

The promised novelty was irresistible: a place dubbed Konstantinapoly Budapesten, “Constantinople of Budapest”.

A wooden footbridge stretching across the water, a replica of Galata Bridge, was glowing under newly installed arc lights.

From the bridge, the lake and its surroundings sparkled with lanterns and painted facades.

Ahead lay narrow bazaar streets, arch-covered passages, and shops crowded with “eastern wares”, lanterns, tapestries, spices, and strange ceramics. A painted replica of the great dome of Ayasofya, and a miniature version of the Galata Tower, overheard musicians playing unfamiliar tunes in cafes called “The Great Sultana” and “Eastern Nights”.

There were battleships built for events, which often sank to entertain guests. In the middle of the lake, there was a castle-like fortress on a small island from which fireworks were shot off.

Budapest by night turned into a simulacrum of Istanbul. For a brief evening, visitors were no longer in Central Europe, but in a fantasy of the East, framed for European consumption.

“Constantinople in London”

A similar spectacle unfolded in London just a few years earlier. Between 1893 and 1894, the Olympia Exhibition Centre hosted a vast multisensory entertainment district titled Constantinople in London.

This theme park incorporated several exhibitions, a grand theatre, a bazaar, bars, and restaurants. Its architectural settings partly emulated iconic monuments in Istanbul to recreate the city’s atmosphere and partly drew on tropical motifs commonly associated with the “Orient” at the time.

Viewed through the filters of colonialism and Orientalism in the Western world, the perceived qualities of “the rest of the world” were enthusiastically yet often inaccurately projected onto representations of distant culture, becoming “an imaginary impression of the related lands”.

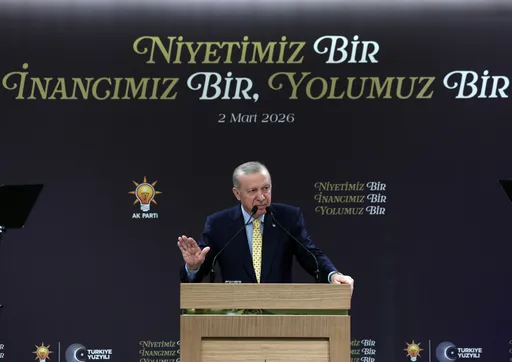

This perspective framed the one-day conference “Reinvented as Theme Park: Istanbul in the Imagination of Nineteenth-Century Europe,” held in Istanbul, which examined how Istanbul was transformed into a spectacle across Europe during the fin de siècle.

The conference explored how the city was reinterpreted, or reinvented, through public displays ranging from theatrical architecture to full-scale entertainment districts.

Istanbul as imagined by the West

Scholars traced how these ephemeral worlds, composed of alleys, bazaars, makeshift mosques, and stage-set monuments, constructed an Istanbul that existed more in the European imagination than in reality.

The case studies presented throughout the conference revealed a broader pattern: a deep fascination with, and persistent romanticisation of, the East by the West. Whether in Budapest’s glowing Galata Bridge or London’s elaborate theatrical recreations, Istanbul became a canvas onto which Europeans projected their fantasies, offering not the city itself, but an alluring dreamscape shaped by Orientalist desire.

“The ephemeral theme park Constantinople in London was what we’d call a blockbuster today: a massive success both in terms of turnout and profit. The investors made quite a fortune,” Peter Tamas Nagy, an architectural historian of the Islamic world, tells TRT World.

In the abstract of his paper, “Constantinople as Spectacle: A Controversial Theme Park in London”, Nagy names the Olympia Exhibition Centre of 1893-1894 as the host for Constantinople in London, “a multisensory entertainment district or theme park” that featured several exhibitions, a grand theatre, a bazaar, bars and restaurants.

Nagy tells TRT World that he suspects that part of the explanation for the theme park being a hit “lay in its manifold means of entertainment: Various sorts of arts, including theatre performance, music, painting, tableau vivant (‘living statue’), and architecture, were at play in concerto, not to mention culinary delights, Turkish coffee, and premium tobacco.”

“The principal concept was to provide a multisensory experience, by which visitors felt as though they were escaping into another world,” pointing out that “Even though from today’s perspective it appears as a somewhat inaccurate and distorted representation of Istanbul, the theme park was highly successful in its goals.”

Due to globalisation and colonialism in the 19th century, the West had significant encounters with the Middle East, the Near East, and the Far East – far beyond what individual seafarers had brought back from overseas in the past.

The West had been discovering so-called exotic, foreign lands, and the discoveries were garnering significant interest from the masses.

‘Almost a European invention’

Edward Said, in his groundbreaking 1978 book describing the phenomenon, wrote: “The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.”

For Zsuzsanna Emilia Kiss, a lecturer at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, the aim of Constantinople in Budapest was “to evoke Istanbul through cafes, stalls, performances, and reconstructed street scenes rather than through historical accuracy”.

She explains that the exhibition “revealed how Budapest imagined Istanbul: not as a modern metropolis undergoing reforms, but as a romantic, lively, atmospheric ‘Orient’ — full of colour, noise, trade, and spectacle”.

Kiss tells TRT World that the “imaginative construct” of the “Magical Orient” sprang from the West: “a romanticised, aestheticised vision of the East that blends fantasy, desire, nostalgia, and spectacle”.

Nagy sees it somewhat differently, while conceding to TRT World that “The traditional (if not dated) East-West narrative strings along the power dynamics in which one side dominated the other. The European colonisation of several Muslim countries is indeed what makes this subject thorny.”

He finds it “highly questionable” to speak of a single West and a single Orient when examining artistic or architectural representations of the time.

According to Nagy, there could be “numerous and occasionally counterbalanced directions of borrowing and emulation” when considering the relations between the East and the West, and a variety of reasons behind architectural tendencies across the globe.

Nagy considers Orientalising architecture is “merely an episode” in the larger story, as he says that architectural imitations were not limited to the West emulating the East. He suggests putting aside “stereotypical biases” and considering Orientalising architecture as “a constituent stand within the global nineteenth century”.

Nagy sees it somewhat differently, while conceding to TRT World that “The traditional (if not dated) East-West narrative strings along the power dynamics in which one side dominated the other. The European colonisation of several Muslim countries is indeed what makes this subject thorny.”

Yet, he says, when examining artistic or architectural representations of the time, “it is highly questionable where we could assume a single ‘West’ and a single ‘Orient’. In reality, there could be numerous and occasionally counterbalanced directions of borrowing and emulation to consider, as well as a variety of reasons behind these architectural tendencies across the globe.”

He continues: “Many examples exist where another territory’s architectural heritage was consciously imitated elsewhere; Orientalising architecture constituted merely an episode in the larger story. It therefore seems timely to put aside stereotypical biases and discuss Orientalising architecture as a constituent stand within the global nineteenth century.”

‘An inspiration source’

Gergo Mate Kovacs, an engineer specialising in the preservation of built heritage and a scholar of Turkish, working as the Cultural Attache at Liszt Institute - Hungarian Cultural Center in Istanbul, tells TRT World that in late 19th-century Hungarian historicist architecture, “the appearance of Islamic forms was characterised not only by general European Orientalism, but also by phenomena specific to Hungary.”

He points out that numerous visits and expeditions were “launched to Near or distant parts of Asia, in the opposite direction, numerous handicrafts, written and illustrated reports, drawings, and photographs arrived in Europe, to public and private collections, which European architects, often working in the spirit of historicism, used as an inspiration source for their buildings”.

However, in many cases, the motifs were placed in a completely different context.

In other words, the reconstruction of the East often resulted in a mishmash of styles not necessarily representative of one location in question but of a more expansive geography: “The origins of the inspirational forms are typically North African or Iberian, with photography, contemporary journals, surveys, and contemporary printed works featuring drawings serving as the mediating medium”.

“However, there are also instances of indirect influence, with the impact of buildings seen at world exhibitions and theme parks becoming apparent.