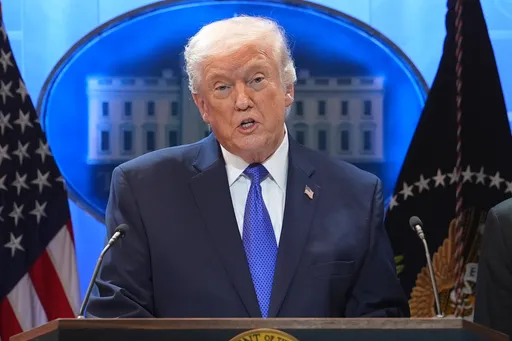

Last March, US President Trump announced that the US will impose tariffs on imports of iron and steel, in an attempt to fulfill a campaign pledge to protect domestic economy and bring jobs back to US workers.

Tariffs apply to only 2 percent of all US imports and exclude its biggest trading partners Mexico, Canada and EU countries. However, the new policy specifically affects China and is expected to be the beginning of an acceleration between two countries that are political and economic competitors as much as they are trading partners.

This, of course, sparked fears of a global trade war where countries restrict trade and turn into numerous disconnected and closed national economies with minimum economic transaction – instead of one global economy.

However, neither policy makers nor economists seem concerned about discussing how trade restrictions might impact less developed countries. This is in part due to the fact that the majority of international trade takes place among OECD and G7 countries.

Nevertheless, a full-on trade war has significant implications for less developed countries, but the implications are likely to be quite different than those for developed nations.

Inequal opportunities

Standard economic theory is straightforward in terms of the adverse effects of trade protectionism. On the one hand, developing countries are likely to face higher tariff barriers while exporting their products to other countries which may be detrimental to export-oriented growth.

The fact that most growth miracles of the last century, including Japan and South Korea, were driven by increasing exports to developed countries proves how important this might be. On the other hand, if developing countries decide to retaliate with higher tariffs on imports in order to keep their current account deficits in check, this will lead to higher prices for imported products and a substitution of high quality foreign products with the domestic ones.

The overall outcome is a reduction in purchasing power due to reduced income and inflation.

However, there is also a strong case for the argument that restrictions on global trade might be as much of an opportunity for developing countries, as they are a risk. Restrictions on foreign products imply better protection for domestic sectors such as high-technology industries which developing countries need to improve their growth prospects.

Countries categorised as developing or emerging economies are by nature ‘late-bloomers’ in terms of industrialisation so they have to compete with the sophisticated and cost-efficient industrial production of early industrialised nations.

In a globalised world, newly emerging (infant) industries have to compete with century-old industrial giants, and more often than not, are crushed before they can even develop the capacity in terms of human capital and know-how for high technology sectors - and reduce the per-item cost associated with large scale initial investments.

Restrictions on imports and a closed economy, in this respect, provide a protective shell for domestic entrepreneurs and investors to expand their production and learn-by-doing. As production expands and becomes efficient enough to compete globally, trade protection becomes redundant. This is how the argument for “infant industries” goes according to the famous German economist, Friedrich List.

Interestingly, the first to put forth the “infant industries” hypothesis was Alexander Hamilton, first secretary of the treasury of the US. He argued that the young American economy should protect its markets from an invasion of British products so that American industrialists are given a chance to make themselves competitive.

Cambridge Economist Ha-Joon Chang argued that the infant industries hypothesis is still relevant in the modern context. In his influential book Kicking Away the Ladder, he argued that developed nations force liberalised trade and globalisation upon less developed nations so that they can enjoy both the cheap labour force and the larger market of developing countries. By doing so, they deprive these nations of political instruments like trade protections which they themselves had the luxury of using while in their own infant-state era.

A window of opportunity

A trade war, in this respect, provides a loophole in the global hegemony of industrialised countries and enables less developed countries to better manoeuver their political agendas.

International financial institutions such as the IMF, World Bank and especially the World Trade Organization (WTO) have been the driving instruments of powerful nations to put pressure on developing countries to lower trade barriers and open their markets.

Now, that the US itself is violating the WTO rules, these institutions have less leverage in pushing developing countries towards free trade. Both Germany and Japan are successful examples of how instability and a lack of hegemony in the global trade system may be an opportunity for latecomers to catch up with the industrialised powers of the world.

In a world where developed nations violate the rules they have set, developing countries can find a degree of independence.

Needless to say, trade restrictions do not automatically give way to industrialisation and improved economic performance. Restrictions on imports merely provides an opportunity for domestic industrial sectors to emerge but this is not sufficient in and of itself.

First, without an investor class that has minimum levels of capital accumulation and a tendency to invest in productive activities, there is not much to protect. This is likely to be a problem, especially in the least developed countries including most sub-Saharan economies.

Second, without government initiatives to provide basic physical infrastructure and supporting institutional arrangements like the rule of law and property rights, productive economic activity is unlikely to function efficiently.

Last but not least, manipulating markets for the better is a complicated endeavour which is why so many growth economists approach trade restrictions with suspicion.

Governments that succeed in maintaining the inflow of necessary intermediate goods and financial capital while restricting the import of domestically substitutable final goods will benefit from a potential trade war.

All in all, a trade war poses an opportunity as much as it does a risk for less developed countries. Even though living standards may deteriorate in the short run due to higher prices, developing countries can benefit from a period of limited international trade in the long-run if they can manage the process by protecting innovative and productive industries, and enhancing their competitiveness.

It's ironic that the exclusive and selfish policies of the leaders of developed countries provide an opportunity for developing countries to create more sophisticated economies and improve the living standards of their citizens. Developing nations should really make the best of this because these episodes are rare, and short.