Saudi Arabia has jealously guarded its claim to being the “guardian of Islam” by being the undisputed leader in donating humanitarian aid to the Muslim world, with foreign aid contributions exceeding $90 billion – or 3.7 percent of its annual gross domestic product in thirty years spanning 1975 to 2005.

But in its current era of defacto Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman (MBS) rule, the Kingdom is replacing its previously expressed care for Muslim causes with the cold-hearted calculations of realpolitik.

Under MBS, Saudi Arabia is undergoing what can be viewed as an identity transformation, moving away from its brand of ultra-orthodox Islam towards a new nationalism - a move that rolls back the influence and control of the country’s religious establishment over the House of Saud. This, in turn, creates the political space for the MBS-led monarchy to be constrained less by religious notions portending to morality, and allow it to exact profits from its state-controlled oil business with ruthless efficiency.

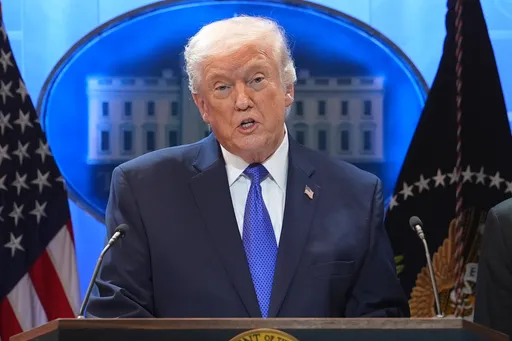

On the rare recent instances it puts the weight of the monarchy behind a cause or crisis in the Muslim world, it does so but with begrudging reluctance, and typically because it has either trampled on or turned its back on an untouchable or sacred Islamic rail. This is no more evident than in the way it acted as a publicist for the US in soliciting Arab support for President Donald Trump’s so-called “Deal of the Century.”

The Saudis later publicly distanced themselves from the deal due to the broader Arab and Muslim anger towards what would’ve solidified a system of apartheid for the Palestinian people, while sanctifying Israel’s illegal claims to ownership of Jerusalem.

Saudi Arabia has danced a similar two-step with Pakistan over India’s human rights violations in Kashmir and New Delhi’s stripping of the Muslim majority territory’s “semi-autonomous” status.

On February 7, Saudi Arabia rejected Pakistan’s second plea for an urgent meeting of the council of Foreign Ministers on Kashmir at the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan responded by slamming of what he views as an apathetic Saudi response by saying, “We can’t even come together as a whole on the OIC Summit meeting on Kashmir.”

The following day, Saudi Arabia, responding to global criticism, performed a diplomatic U-turn, announcing it would work together with Pakistan to “advance the Kashmir cause,” including from the platform of the OIC.

Until now, the Saudi government has shown almost zero interest in the safety and well being of eight million Muslims in Kashmir, even seemingly pretending as though the Narendra Modi-led Indian government hasn’t set in motion the workings of a Hindu-settler-colonial project, akin to Israel’s colonisation of the Palestinian West Bank, euphemistically describing it as an “internal issue.”

Saudi Arabia’s muted response to Kashmir is explained by its petroleum sales to India, with the Kingdom now the Asian country’s second-largest supplier.

In October of last year, the trade ties between Riyadh and New Delhi became even stronger on the back of a bilateral deal that will ensure Saudi owned Aramco helps India build the capacity to hold emergency crude oil reserves as a “buffer against volatility in oil prices and supply disruptions.”

Expect ties between Riyadh and New Delhi to grow ever closer in the coming years and decades, a relationship that will come at the expense of both Pakistan and the Kashmiri people.

India’s economy is not only seven-times the size of Pakistan’s but is also fast becoming one of the Arab world’s most strategic partners.

“As a growing market for Arab oil and gas, as a source of highly trained and competent personnel, and as a friendly country with a powerful military and a strong interest in geopolitical stability, India is a valuable neighbour in a dangerous part of the world,” observes the Wall Street Journal.

Saudi Arabia’s apathy towards the ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar mirrors its attitude and behaviour towards Kashmir. Three weeks ago the United Nations’ highest court, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), ordered Myanmar to take emergency “protective measures” to guarantee the safety of the Muslim minority, but the Myanmar military has defied the ruling in continuing to carry out weekly, almost daily attacks on Rohingya villages in Rakhine state.

Neither Saudi Arabia nor the OIC has offered to take a lead role or play any role in resolving what is one of this century’s worst genocide campaigns. Why? Saudi Arabia ruthlessly and jealously protects its status as China’s top supplier of crude oil, and the Myanmar-China Oil and Gas Pipelines carry oil from the Arabian Peninsula to China’s landlocked Yunnan Province through Myanmar.

“One could argue that Saudi Arabia is less likely to be outspoken on this (Rohingya) issue because it actually relies on the Burmese government to protect the physical security of the pipeline,” Bo Kong, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies who has written about China’s global petroleum policy, told the Associated Press.

There was a time, until very recently, that Saudi Arabia seized opportunities to enhance its reputation in the Muslim world, remembering it was the number one international donor towards cyclone relief in Bangladesh in 2007 and provided Pakistan with $220 million in humanitarian aid for the 2010 floods. But now under MBS, Saudi Arabia is moving away from its religiously inspired generosity and morality, and in its place is embracing nationalism and the maximisation of petroleum profits.