The US abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has reverberated far beyond Latin America, triggering alarm in Beijing and sharpening global debates over sovereignty, international law, and great-power rivalry.

For China, the military attack is not merely a regime-change move against a long-standing US adversary, but a warning shot about Washington’s willingness to assert unilateral power — and to redraw red lines in the name of hemispheric dominance.

Chinese analysts say the episode marks a turning point.

“This is not a regional crisis but a fundamental assault on the post-World War II international order,” Chinese geopolitical expert Gao Jian tells TRT World.

“By removing a sitting head of state through unilateral military force, the US is openly replacing international rules with a ‘might makes right’ logic,” argues Gao, a professor at Shanghai International Studies University, and visiting fellow of China Forum, Center for International Strategy and Security Studies at Tsinghua University.

That assessment closely mirrors Beijing’s official position. Within hours of the US attack, in which at least 80 people were killed in Venezuela, Chinese President Xi Jinping condemned what he called “unilateral and bullying acts,” warning that such actions are “severely undermining the international order.”

Speaking during a meeting with Irish Prime Minister Micheal Martin in Beijing, Xi urged major powers to respect international law, sovereignty, and the principles of the UN Charter.

Meanwhile, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said Beijing cannot accept any country acting as the “world’s judge” or “world’s police” without naming the US, as he referred to the “sudden developments in Venezuela” during talks with his Pakistani counterpart in Beijing on Sunday.

The unusually strong language on the situation dealing with a third country underscores how seriously China views the US move.

Beijing sees this not merely as an intervention in Venezuela, but as a broader assertion of American primacy under what President Donald Trump has openly framed as a revival of the Monroe Doctrine, which he has dubbed the “Donroe Doctrine,” playing off his own name.

A warning beyond Caracas

From Beijing’s perspective, the abduction of Maduro represents a dangerous precedent. Gao argues that Washington has crossed a legal and political threshold.

“China sees this as a blatant use of force against a sovereign state,” he says. “It signals that any government can be targeted if it conflicts with US interests. That is hegemonic bullying, and it destabilises the entire international system.”

China has urged Washington to stop violating other countries’ sovereignty, saying Venezuela’s future must be decided by its people and calling on the US to ensure the safety of the detained president and first lady.

The concern in Beijing is not limited to Venezuela itself. Analysts see the operation as part of a wider US effort to reassert exclusive influence over Latin America and to push external powers — particularly China — out of the region.

Over the past two decades, China has significantly expanded its economic and diplomatic footprint in Latin America, emerging as a major trade partner, investor and political interlocutor across the region.

Timing and symbolism

Just hours before the US raid, Maduro met in Caracas with Qiu Xiaoqi, China’s special envoy for Latin American affairs. The meeting reaffirmed what both sides described as a strategic partnership aimed at promoting a multipolar world.

Chinese officials have dismissed any suggestion that the meeting provoked Washington’s action. Lin Jian said Qiu’s visit was routine and part of China’s normal diplomatic engagement with Latin America.

Gao agrees. “I personally do not see any relevance between the timing of the US strike and the Chinese special envoy’s meeting with Maduro,” he says.

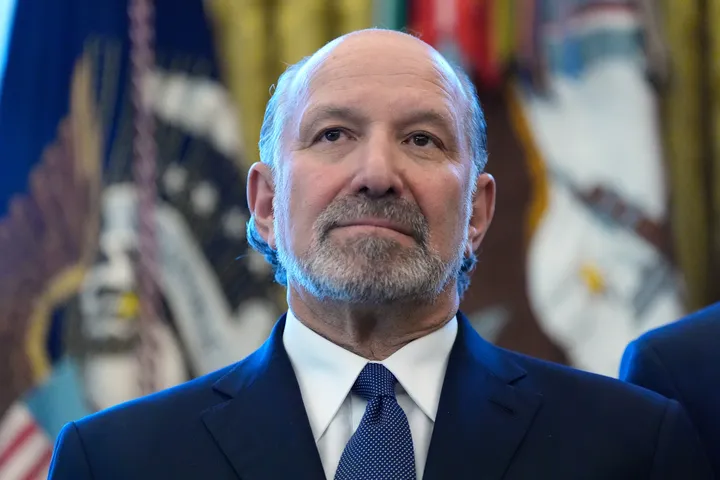

But in Washington, the coincidence has not gone unnoticed. John Kavulich, an American political analyst and president of the US-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, says the overlap may not have been planned — but it was politically useful.

“The timing was coincidental,” Kavulich tells TRT World. “However, it was a welcome coincidence. It demonstrated the lack of concern by the Trump administration about interrupting a country where China has substantial commercial, financial, military and political interests.”

China’s economic stakes

Those interests are significant. Over the past two decades, China has invested more than $60 billion in Venezuela, largely through oil-backed loans and joint ventures. Venezuela has been one of China’s key crude suppliers in Latin America, making the country central to Beijing’s energy security strategy.

China says its cooperation with Venezuela is lawful, protected by international law, and insulated from political change, insisting that Beijing’s investments and agreements remain legally binding regardless of how the situation evolves.

But Kavulich argues that Venezuela’s debt to China is now a key leverage point for Washington.

“The most significant US-China issue arising from this operation is what happens to the billions of dollars Venezuela owes China,” he says. “Those debts have been repaid largely through oil exports. Will the US allow that to continue, renegotiate it, or try to extract concessions from Beijing?”

But beyond questions of debt, oil and economic leverage lies a broader strategic issue — Washington’s open assertion of hemispheric dominance, rooted in an old doctrine now being recast for a new era.

Reviving the Monroe Doctrine

First articulated in 1823, the Monroe Doctrine asserted US dominance over the Western Hemisphere. Trump invoked that legacy in a triumphant press conference on Sunday following Maduro’s abduction by US special forces, declaring: “The Monroe Doctrine is a big deal, but we’ve superseded it by a lot — by a real lot. They now call it the ‘Donroe Doctrine.’”

Trump administration officials have been unusually explicit in framing Venezuela as part of America’s traditional sphere of influence. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has described the Western Hemisphere as a strategic priority and warned external powers against entrenching themselves in the region.

“We don’t need Venezuela’s oil. We have plenty of oil in the United States. What we’re not going to allow is for the oil industry in Venezuela to be controlled by adversaries of the United States,” Rubio told NBC’s Meet the Press as he categorically named China, along with Russia and Iran, as US adversaries.

“This is the Western Hemisphere. This is where we live. And we’re not going to allow the Western Hemisphere to be a base of operations for adversaries, competitors, and rivals of the United States, simple as that,” Rubio asserted.

For Beijing, this rhetoric confirms long-held suspicions. Gao describes it as “outdated imperialist thinking.”

“This is an attempt to turn Latin America back into a US backyard,” he says. “It ignores the sovereign choices of Latin American countries and their right to diversify partnerships.”

China’s Foreign Ministry has positioned Beijing as a counterweight, saying it will remain a “good friend” to Latin American nations and opposing any action that violates regional sovereignty.

Test of multipolarity and the Taiwan parallel

The Venezuela operation has also reignited debate about whether the international system is truly moving towards multipolarity — or whether US military power still trumps all.

China has backed a UN Security Council discussion on the US raid, arguing that multilateral institutions must play their proper role. Xi’s remarks about “changes and chaos” in the global system reflect a broader Chinese narrative: that US unilateralism is accelerating instability rather than preserving order.

Gao believes Washington’s approach is ultimately self-defeating. “Placing domestic US law above international rules is dismantling the very order the US claims to defend,” he says. “In the long run, this will not stop the trend toward multipolarity.”

Some Western analysts have drawn parallels between US action in Venezuela and potential Chinese military moves against Taiwan — comparisons that Beijing strongly rejects.

Gao is categorical. “There is no basis for comparison,” he says. “Venezuela is a sovereign state. Taiwan is an internal matter of China,” he adds, asserting the official Chinese position.

China deems Taiwan a "breakaway province" while Taipei has insisted on its independence since 1949.

Kavulich offers a more sceptical view of how international law is applied globally. “Every country applies international law selectively,” he says. “There have been and will be consequences, but those consequences rarely stop powerful states from acting or attacking the territory of another government.”

Whether framed as law enforcement or deterrence, Trump’s Venezuela operation sends a clear signal: Washington is prepared to use force to defend what it sees as its sphere of influence.

For China, the message is unmistakable. Venezuela is no longer just a partner in Latin America — it is a case study in how far the US is willing to go to reassert dominance, say analysts. And for the rest of the world, they say, the episode raises an unsettling question: if sovereignty can be overridden so decisively in Caracas, which capital might be next?