A 30-year-old Argentine woman, anonymously named after the city she lives in, “Esperanza”, which means “hope” in Spanish, has been determined free of HIV after eight years without having received therapy.

An article in the Washington Post suggests she “appears to have become the second documented person whose body may have eliminated her HIV on its own,” according to a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Monday.

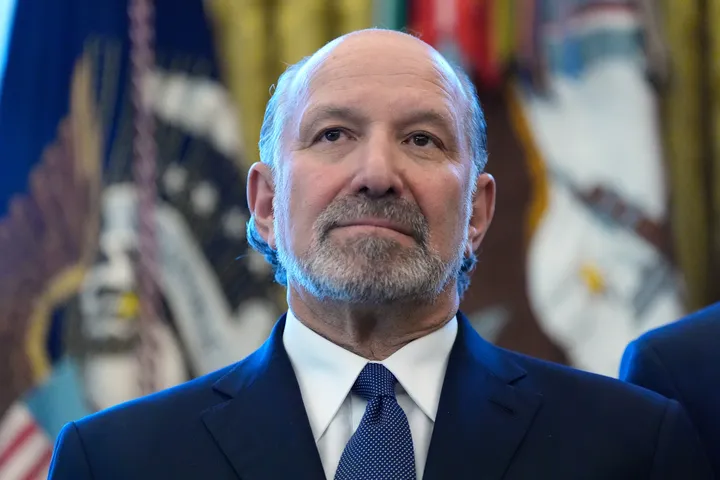

An editorial written by Joel N. Blankson MD for the Annals of Internal Medicine notes “Fewer than 1% of people living with HIV are able to control viral replication to below the limits of detection by commercial assays without antiretroviral therapy (ART).”

Blankson goes on to say that these patients “are called ‘elite controllers’ or ‘elite suppressors,’ and they represent a model of a cure for HIV-1.

Blankson does mention a caveat: “However, it has not always been clear whether they are models of a functional cure, where replication-competent virus remains but is controlled by host factors (analogous to the control of herpes viruses), or a sterilising cure, where the virus is eradicated by the host (analogous to the control of most viruses).”

The study, titled “A Possible Sterilising Cure of HIV-1 Infection Without Stem Cell Transplantation” speaks of the Esperanza patient as an elite controller who may have been a model of a sterilising cure.

The Washington Post reports the researchers as writing that “Scans of more than 1 billion of the woman’s cells detected no viable virus, even though for most of the time she was not undergoing antiretroviral therapy meant to keep the virus from replicating.”

Marisa Iati of the Washington Post goes on to say that the finding raises the possibility that “a person’s own immune system may in rare cases provide a sterilizing cure — the elimination of virus capable of copying itself — the researchers wrote.”

“What happened is unique,” Steven Deeks, an HIV researcher at the University of California at San Francisco, who was not involved in the study tells the Washington Post. “It’s not that she’s controlling the virus, which we do see, but that there’s no virus there, which is quite different.”

According to data from UNAIDS, “37.7 million [30.2 million–45.1 million] people globally were living with HIV in 2020.” If scientists could unlock the reason why the Esperanza patient was showing signs of a sterilising cure, it would provide a breakthrough in treating, even possibly curing, HIV, which with lack of treatment, can turn into AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) and sicken and kill its host.

HIV has no known cure, but can be treated by a cocktail of drugs, and in the case of three people, eliminated altogether through stem cell transplants to cure their cancer.

The Washington Post points out that transplants are “dangerous and frequently fraught with complications,” thus making them an unviable choice for the millions infected with the virus who are on the daily pill regimen and “a recently approved injection” called Cabenuva, that is the combination of Janssen’s rilpivirine, sold as Edurant, and a new drug, ViiV’s cabotegravir.

The Washington Post reports that researchers are focusing on four ways to cure HIV: “activating the body’s immune response to the virus, gene therapy, ‘shock-and-kill’ attempts to force the virus from cells so the immune system can try to eradicate it, and ‘block-and-lock’ efforts to keep the virus lodged in cells so it can’t replicate.”

The first person to have been cured without a bone marrow transplant or medication may have been Loreen Willenberg of California. The Esperanza patient from Argentina, the subject of the study, may be the second.

Deeks, who worked on a study of Willenberg last year, tells the Washington Post that both women may have been cured because they had unusually powerful T cells, a component of the body’s immune system. Understanding that mechanism, he adds, could be key to developing therapeutic vaccines that could clear out HIV without negative long-term consequences.

Blankson, in his editorial for Annals of Internal Medicine, writes that the Esperanza patient may have developed an HIV-specific immune response before becoming infected, the Washington Post reports, adding his suggestion is to have researchers use her cells to replicate her immune system in mice which would then be infected with HIV to see whether they would become free of the virus over time.

The Esperanza patient was diagnosed with HIV eight years ago. Since 2013, the researchers wrote, ten tests found no detectable levels of the virus in her blood or tissue.

The Argentine woman only took a pill regimen during her pregnancy’s second and third trimesters, in late 2019 and early 2020, before delivering a baby that was HIV-free.

Scientists were unable to detect HIV in her body, but did find fragments that suggested that she had indeed been at one point infected and the virus had replicated before her immune system cleared her body of HIV.

The researchers admit that “Absence of evidence for intact HIV-1 proviruses in large numbers of cells is not evidence of absence of intact HIV-1 proviruses. A sterilizing cure of HIV-1 can never be empirically proved,” yet conclude “These observations raise the possibility that a sterilising cure may be an extremely rare but possible outcome of HIV-1 infection.”