The murder and dismemberment of Jamal Khashoggi left a family without a father. That is a tragedy too many families endure, from Syria to Yemen to Afghanistan.

He was a victim of a regional war for dominance in the Middle East, although his brutal death was not on a battlefield. It was in an air-conditioned office of the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul. Too many spouses, sons and daughters of murdered or imprisoned journalists around the world worry if their loved one will not make it home one day. That day, October, 2, 2018, came for the Khashoggis.

In pursuing its endless war in Yemen against Houthi rebels, supported by its rival Iran, Saudi Arabia has relied on the grim adage, attributed allegedly to Joseph Stalin, that one death is a terrible tragedy and a million deaths are a statistic. The war in Yemen has taken the lives of tens of thousands of people, most of them children dying of disease or starvation.

Khashoggi’s death was one among that same galaxy of misery. His crime was not being a Yemeni child, but being a dissident member of the Saudi elite, who had criticised his own government in the pages of The Washington Post. Turkish and US intelligence have gathered evidence pointing to a premeditated murder carried out by a Saudi hit squad working at the direction of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the 34-year-old known as MBS and responsible for the kingdom’s ambitious economic and social reforms.

But liberalising Saudi society is not the same as granting real rights, not just privileges, to Saudi subjects. As it stands now, Saudis have no say themselves in the direction of their country. Khashoggi, using his gift for words, contradicted MBS’s unsubtle message that authoritarianism, not democracy, was what was best for the Arab world.

In a column written for The Washington Post on September 11, 2018, Khashoggi urged Riyadh to stop the war in Yemen, saying it had endangered Saudi security. After the drone-bombing of a Saudi oil refinery, allegedly carried by Houthi rebels, and what appears to be a humiliating defeat for Saudi ground forces at the Yemeni border, his words sound prescient.

“Saudi Arabia’s war efforts have not provided an extra layer of security but have rather increased the likelihood of domestic casualties and damage,” Khashoggi wrote. “Saudi defense [sic] systems rely on the U.S.-made Patriot missile system. Saudi Arabia has been successful in preventing Houthi missiles from causing substantial damage. Yet, the inability of Saudi authorities in preventing Houthi missiles from being fired in the first place serves as an embarrassing reminder that the kingdom’s leadership is unable to restrain their Iranian-backed opponent.”

In his final Washington Post column, Khashoggi discussed the urgent need for rights to free expression in Arabic-speaking countries, rights that could influence governments not to pursue wars they can’t win. Had MBS listened to Khashoggi instead of ordering his death, perhaps Saudi would not have suffered the attack.

In the last year, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has tried to spin Khashoggi’s death as merely unapproved, a mistake and not a murder. It puts Khashoggi’s death into the same category of unintentional deaths brought on by the Saudi campaign in Yemen, despite the grotesque intimacy of killing and hacking apart the body of a 59-year-old exile, a permanent resident of the US, who had come to the consulate that day to see about marriage paperwork for his Turkish fiancee, Hatice Cengiz. She waited for him to emerge from the consulate for hours, in vain.

On the first anniversary of the killing, MBS has attempted to rehabilitate his image as a reformer who is bringing greater social freedom to Saudis while privatising and “digitalising” the economy. In an interview aired Sunday night with the American news program 60 Minutes, MBS admitted to correspondent Norah O’Donnell that Khashoggi’s killing was “heinous” and that he was “responsible” as the Saudi leader, but denied ordering Khashoggi’s death himself.

Norah O'Donnell: Did you order the murder of Jamal Khashoggi?

Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (Translation): Absolutely not. This was a heinous crime. But I take full responsibility as a leader in Saudi Arabia, especially since it was committed by individuals working for the Saudi government...When a crime is committed against a Saudi citizen by officials, working for the Saudi government, as a leader I must take responsibility. This was a mistake. And I must take all actions to avoid such a thing in the future.

O’Donnell, while getting MBS on the record, does not ask him why he thinks anyone would have wanted Khashoggi dead in the first place. The rest of the interview focuses on Iran and Saudi attempts at reform.

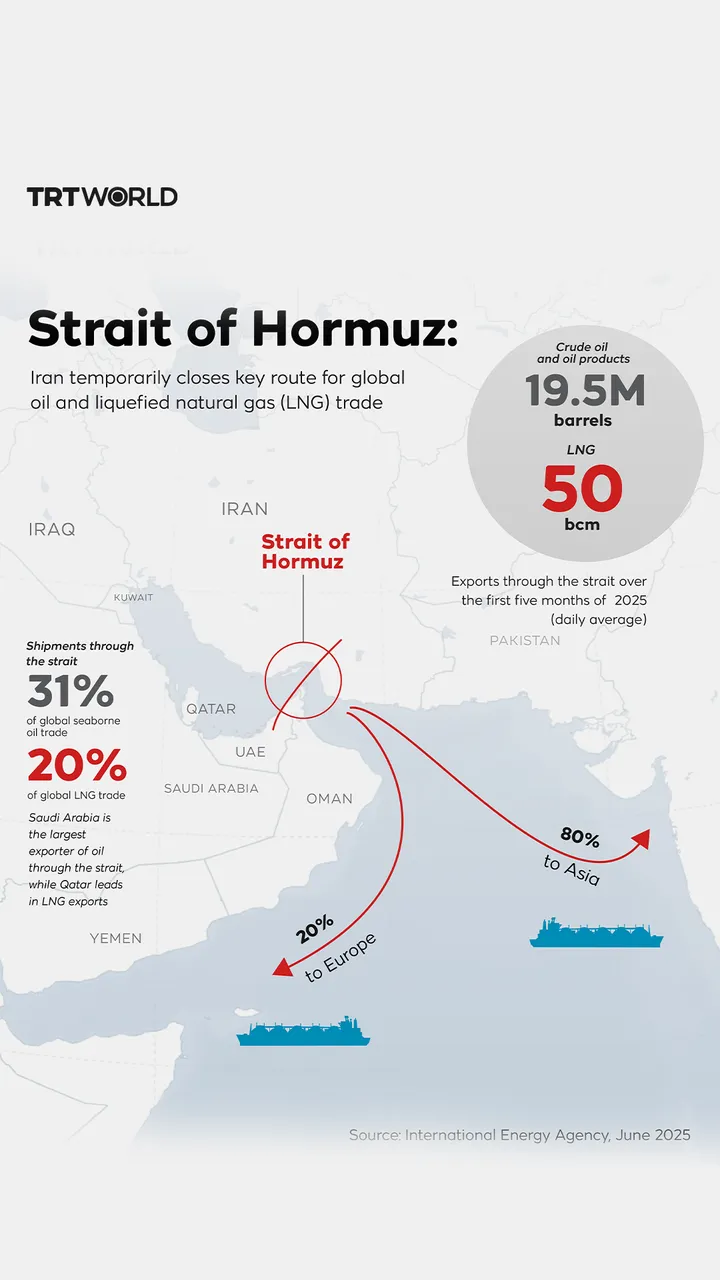

What the rest of the interview reveals is that MBS wants the whole world to share the blame with him, wielding his country’s influence as an oil producer but not as a winner of hearts or minds. There can be no consequences for Saudi Arabia’s rulers as long as Saudi Arabia produces a third of the world’s oil. MBS isn’t worried about the International Criminal Court. His kingdom’s enormous resources put him beyond the reach of any kind of prosecution.

What is one human life in the shadow of a trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund? How about the health of the entire global economy, which MBS declared to be the stakes of his stand-off with Iran?

MBS can go on 60 Minutes and spin the killing. He can talk up the Saudi Aramco initial public offering or his plans for “smart cities” featuring artificial moons, alcohol, and eugenics programmes. McKinsey, a consulting company, can take money in exchange for telling MBS his ideas are brilliant. Meanwhile, Yemeni children can die anonymously, before they learn their own names.

But the stain on the kingdom’s reputation will remain, no matter what. In the same sense, the US can never redeem itself from the torture-murders it carried out during the height of the War on Terror. There are millions of people who will always consider the US government to be a force for evil in the world. That is understandable.

This is not fair for Americans, who are Americans by accident. It is not fair for Saudis, who have even less control over their country’s foreign policy than Americans do. Just as the War on Terror was bad for Americans, the kingdom’s regional proxy war with Iran, and its diplomatic stand-off with Qatar, are ultimately bad for the royals’ subjects. MBS does not ask them when he decides a Saudi journalist needs to die, just as the CIA never asked the American public if they thought torturing Gul Rahman to death in Afghanistan in 2003 was a good idea.

Although he did not live to see it, the last year of history has proven Khashoggi right. The less control Arabs have over the affairs of their governments, the more dangerous and unfair the world will be. Leaders will get away with heinous crimes, and the blame will boomerang back on the people they lead, who have a hard time telling statistics and tragedies apart.

Whether they are statistics or tragedies, murders have consequences. We can understand best on the personal level, if we can bring ourselves to imagine the people the dead leave behind. If you knew what had happened to Khashoggi that day, and saw his fiancee standing outside the consulate, what would you tell her? Would you tell her what was next? Would you tell her Khashoggi was right?