For much of the past decade, the Indo-Pacific has been portrayed as a distant geopolitical theatre, primarily shaped by the rivalry between the US and China.

However, from Ankara’s perspective, the region is neither remote nor theoretical.

Türkiye’s growing diplomatic, economic and defence presence in South and Southeast Asia indicates an emerging reality. Türkiye is already an Indo-Pacific actor in practice, even if it has not yet defined itself as such.

This growing engagement is not the result of a single grand strategy or formal doctrine. Instead, it has emerged organically through a complex network of bilateral relationships, defence partnerships, trade diversification and people-to-people connections, particularly with Pakistan, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Collectively, these relationships demonstrate a subtle yet significant expansion of Türkiye’s strategic geography, extending from the Eastern Mediterranean to the heart of the maritime Southeast Asian region.

As Türkiye's presence in the Indo-Pacific region grows, a new opportunity is emerging: the development of a Türkiye-centric interpretation of the region's importance to Ankara and the region.

While major actors such as the US, the European Union, Japan, India and ASEAN have already established their own Indo-Pacific frameworks, Türkiye's clear definition of its own boundaries would allow it to translate its growing engagement into strategic clarity.

Rather than starting from scratch, Türkiye is well-positioned to shape its own narrative of the region, one that is grounded in existing partnerships, connectivity, and strategic autonomy.

This would reinforce its role as a purposeful and self-defining actor in the region.

An emerging Indo-Pacific reality

Türkiye’s engagement with the Indo-Pacific region is best understood as an extension of the Asia Anew Initiative, launched in 2019 to recalibrate Ankara’s approach to the rapidly changing global economic landscape.

This initiative was never intended to be a narrow regional pivot.

Rather, it was designed as a multidimensional opening spanning diplomacy, trade, logistics, investment, science, higher education and cultural exchange, aimed at enhancing Türkiye’s strategic autonomy in an increasingly multipolar world.

Since then, Türkiye’s engagement with Asia has deepened in both scope and substance.

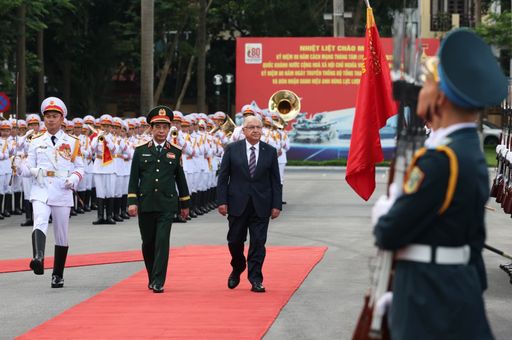

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s tour of Malaysia, Indonesia and Pakistan in February 2025, which resulted in 48 bilateral agreements, was emblematic of this momentum.

These agreements covered defence, energy, finance, education, health, and culture, reflecting institutionalised cooperation rather than mere symbolic outreach.

Considered as a whole, Türkiye’s relationships with Pakistan, Malaysia and Indonesia demonstrate how its presence in the Indo-Pacific region has evolved through action rather than rhetoric.

Pakistan is Türkiye’s western anchor in the Indo-Pacific region.

A relationship long characterised by political goodwill, it has acquired strategic depth through defence-industrial cooperation.

The MILGEM Corvette Project is widely cited as a leading example of South–South naval collaboration and has demonstrated Türkiye’s capacity for technology transfer and joint shipbuilding.

Pakistan’s adoption of Turkish unmanned aerial systems further strengthens their shared path of military modernisation. Analysts are increasingly pointing to Pakistan as a potential future partner in Türkiye’s fifth-generation KAAN fighter programme, particularly in light of Indonesia’s significant acquisition.

Beyond defence, Pakistan’s involvement in the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor could provide Türkiye with indirect logistical and strategic access to the Indian Ocean, which is often overlooked in discussions about Ankara’s presence in the Indo-Pacific region.

Malaysia adds an ideological and economic dimension to this emerging arc.

The political synergy between President Erdogan and Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim reflects a shared emphasis on multipolarity, global justice and strategic autonomy, an alignment that has been widely discussed in scholarship on Muslim middle-power diplomacy.

Cooperation between Türkiye and Malaysia has also expanded into areas such as Islamic finance, the halal economy, cybersecurity, energy and media, establishing both countries as influential players in shaping the region's norms and economy.

Indonesia represents the geostrategic centre of gravity in Türkiye’s engagement with the Indo-Pacific region.

As the largest economy in ASEAN and a pivotal maritime actor, Indonesia provides Türkiye with scale, reach and regional legitimacy.

In 2025, a historic defence package was agreed, including the sale of 48 KAAN fighter jets and the joint production of Bayraktar TB3 and Akinci UCAVs, marking Türkiye’s most significant defence industrial breakthrough in Southeast Asia to date.

Together, Pakistan, Malaysia and Indonesia demonstrate Türkiye's substantial relevance in the Indo-Pacific region.

Rather than entering the region as an outsider, Ankara is already embedded within its strategic, economic and security networks.

Filling the gaps in Türkiye's Indo-Pacific picture

As Türkiye’s engagement with the Indo-Pacific region continues to grow, the next logical step is for Ankara to articulate its own perspective on the region.

This is not an attempt to correct an absence, but a natural evolution of an already active policy.

The term 'Indo-Pacific' is not a neutral geographical label, but rather a political construct shaped by power, identity and strategic intent.

The way in which the region is defined influences who sets agendas, who shapes norms, and which actors are seen as central.

In this regard, most major players have already turned practice into a concept.

The US views the Indo-Pacific in terms of strategic competition with China. India emphasises its role as a leading Indian Ocean power.

The European Union is approaching the region through connectivity and normative influence.

Importantly, ASEAN has also articulated its own outlook on the Indo-Pacific, which is grounded in inclusivity, openness, and ASEAN centrality.

NATO has described it as a 'greater alignment line'.

Meanwhile, Türkiye has pursued a different path, deepening its engagement with the Indo-Pacific region first and developing a conceptual framework for it later.

This distinctive trajectory is increasingly emphasised in academic analyses: Even though it refrains from adopting a fixed regional label, Ankara already operates as an Indo-Pacific stakeholder through diplomacy, trade, and defence cooperation.

This diplomacy has enabled Türkiye to establish partnerships independently of externally defined strategic narratives.

At the same time, articulating a clearer Indo-Pacific vocabulary would enable Türkiye to translate operational momentum into strategic clarity.

While Asia Anew Initiative provides Ankara with a versatile policy toolbox, a Türkiye-centric Indo-Pacific concept would offer a shared framework through which partners, scholars and policymakers could better understand the scope and logic of Türkiye’s engagement.

Rather than limiting options, such a framework would reinforce Türkiye's capacity to present itself as a middle power that defines its own role in the Indo-Pacific.

Toward a Turkish Indo-Pacific map

As Türkiye’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific region grows, it is becoming increasingly important for Ankara to articulate its own regional understanding to consolidate its position as a rule-shaping middle power.

A Türkiye-centric concept of the Indo-Pacific enables Ankara to reflect its unique geography, interests, and strategic culture, thereby transforming growing engagement into strategic clarity.

Taking inspiration from ASEAN's inclusive outlook, Türkiye's vision of the Indo-Pacific can be understood as an interconnected network of maritime and economic spaces stretching from the eastern coast of Africa across the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia to the western and central Pacific.

In this definition, the Indo-Pacific is not viewed as a military frontier, but rather as a corridor of connectivity where sea lanes, trade networks, energy routes and political and economic interactions converge.

Boundaries do not depict military deployments or alliance lines. Instead, they highlight the geoeconomic and geopolitical space in which Türkiye is already active through diplomacy, trade, defence-industrial cooperation, logistics and connectivity initiatives.

The highlighted countries are neither allies nor adversaries.

Instead, they represent different levels of engagement within Türkiye’s flexible foreign policy framework: strategic partners, significant stakeholders, competitors and situational partners.

This approach reflects Ankara’s broader middle-power strategy, which prioritises adaptability, inclusivity and issue-based cooperation over rigid bloc alignment.

This conceptual map also does not position Türkiye within an anti-China bloc or extend NATO’s strategic frontiers.

Instead, it signals a commitment to inclusivity, autonomy, and multidimensional engagement. It tells the region, and the world, that Türkiye views itself as part of the Indo-Pacific network rather than an external power taking sides.

For a country that has long defined itself as both European and Asian, and as both Mediterranean and Black Sea, creating its own Indo-Pacific sphere of influence represents a logical progression.

It is the next logical step in Türkiye’s evolving foreign policy, acknowledging the existing realities on the ground.

Most Indo-Pacific frameworks developed by the US, Japan, India, the EU and NATO tend to exclude Africa, as they are primarily security-focused constructs centred on military balance and strategic competition in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

In these approaches, Africa is treated as a geographical boundary rather than a strategic connector.

However, Türkiye includes Africa in its understanding of the Indo-Pacific because it is connectivity-based, centred on maritime trade routes, energy corridors, logistics networks, and diplomatic engagement that link the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Pacific.

This reflects Türkiye's view of the Indo-Pacific as an interconnected belt of cooperation rather than a closed security bloc.

In an era when regions are defined not just by geography, but also by ideas, those who fail to create their own maps risk being confined by someone else's.

Türkiye’s engagement with the Indo-Pacific region is already a reality. Giving it a name, a framework, and a map would simply make that reality visible.