Walking in your neighbourhood should feel familiar and safe – after all, it’s home. It’s something we all do – maybe on a warm summer night, maybe you’ve had a long day at work, or maybe you’re just bringing home some groceries.

What we don’t think about is what happens when such everyday freedoms are taken away from us. In an interview with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air, Ta-Nehisi Coates talked about growing up in West Baltimore, and being constantly vigilant and alert about where his body was and what space it occupied.

“Don't go to certain neighborhoods unless you know somebody over there, unless your grandmother's there, unless you got a cousin there ... You need to go with four, five, or six other people. When you walk through the street – I can hear my Dad telling me this right now – walk like you have someplace to be, keep aware, keep your head on a swivel, make sure you're looking at everything,” Coates said.

This is how bodies react to a state of constant threat, and how they instinctively work to alleviate the dangers they may face. It’s a story that has framed the African-Australian experience for a long time.

Earlier this year, Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton talked about these Africans and their bodies, where they go, and how dangerous they apparently are.

“The reality is, people are scared to go out to restaurants at night-time because they’re followed home by these gangs. Home invasions and cars are stolen. We just need to call it for what it is ... of course it's African gang violence.”

“We need to weed out the people who have done the wrong thing and deport them where we can.” Dutton continued, implying control over bodies he deems threatening and disobedient.

To contextualise Dutton’s comments, according to the Victorian Crime Statistics Agency, crime in the state has decreased by 4.8 percent over the past 12 months, and in the last decade, youth crime has fallen by 12 percent.

Stuart Bateson is the Priority Communities Division Commander at Victoria police, and said the narrative surrounding African youth gang violence was “racist and divisive.” He said “that it actually harms people and makes them feel unsafe, and that’s the challenge for us as a community because it's just not the reality.”

Victoria police caught off guard

In February, the bodies of Africans were on the mind of one of the most senior officers at the Victoria Police. Brett Guerin was the Assistant Commissioner and head of Professional Standards at the Victoria Police before he resigned.

Under a pseudonym “Vernon Demerest” he wrote offensive and racist comments under YouTube videos. Guerin spoke of how to govern the body of he who refers to as the “jigaboo” in a video of a Somali pirate attack.

"I'm afraid this is what happens when the lash is abolished. The jigaboo runs riot and out of control. The 'boo needs the lash. The 'boo wants the lash. Deep, deep down the 'boo knows the lash provides governance and stability," he wrote.

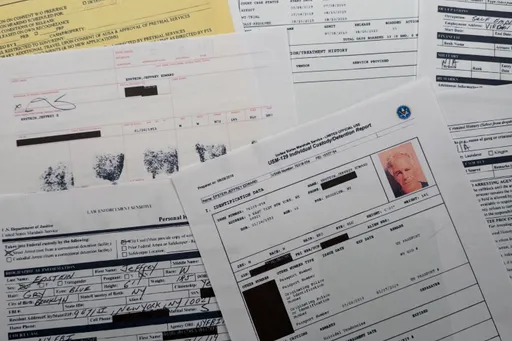

Victoria police have a history of abusing power when it comes to African Australians. In 2013, they settled a groundbreaking case promising to investigate how officers from the organisation were racially profiling young African men.

Melbourne University Professor Ian Gordon analysed data from the police LEAP database during the time of the trial. He found African men around Melbourne suburbs Flemington and North Melbourne were roughly 2.5 times more likely to have their actions recorded by police than the rest of the population.

It is important to note that African men from these areas committed significantly fewer crimes than men from any other ethnicity. And the language the police was most likely to use when dealing with these African men included; "gang", "no reason" and "move on."

But in 2015, when the same group of people involved in the court case released a study detailing how racial profiling hadn't stopped, Victoria police responded strongly. A spokesperson said, “Victoria police does not believe there is a problem with racialised policing.”

Three years later, one of Victoria’s most senior officers would be exposed for his sentiments concerning people of African origin.

I asked Bateson how the force reacted to perceptions about Africans after Guerin’s comments. He told me, “We don’t shy away from the fact that we still have some way to go in getting to where we want to be as an organisation.”

Bateson said “quite frankly, it was a shock when we discovered” Guerin’s comments. And despite his resignation Bateson was adamant, “from our point of view, he resigned ahead of perhaps being dismissed. We do not accept that kind of behaviour or that type of thinking.”

Bateson detailed the programmes throughout Victoria police aimed at better policing in communities. He said, “we have re-engineered our training at the academy, and did some training on unconscious bias to see if we can change some of the behaviour from some of our members on the ground.”

But Guerin was a police officer at Victoria police for 40 years where he earned, respect, authority and eventually, power. Although such attitudes are finally being reigned in, such work can leave collateral damage.

The Age, a newspaper in Australia, initially broke the story about Guerin’s online comments, and revealed how, despite complaints about his behaviour Guerin continued to be promoted.

The paper reported that in 2006, Guerin allegedly used the term "towel head" accompanied by multiple curse words, when he addressed a group of 30 police officers and support staff in Flemington police station.

During his time Guerin was the superintendent for the region at the height of the racial profiling of young African men, between 2005 to 2009.

Around this time, the Victoria police began a programme called Operation Molto conducted from the Flemington Police Station. In an investigation, the ABC uncovered that the operation was established to find criminality in young African Australians living in or visiting the Flemington public housing estate.

While these programmes were being implemented, the local Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre lodged 17 complaints to the former Head of Professional Standards over racialised policing.

Anthony Kelly worked with Guerin in his role as the executive officer of the Flemington Kensington legal centre, and looking back at their interactions, he was “suspicious” of his role as superintendent for the region.

Kelly believed “he was placed in that position as a way of sort of mitigate the outcry at the time that was coming from our legal centre.”

Kelly saw Guerin’s role as two-fold, saying he was “both supporting the police officers in the sort of practices ... we believe he was backing them up in terms of the racial profiling but at the same time he was trying to deflect criticism from organisations like ourselves.”

He said, “we think that was his role and practice, to deflect criticism [whilst] at the same time support the troops.”

The common thread throughout the coverage of Guerin was the shock and surprise from his peers but Kelly didn't agree.

“I’m sure his online persona [brought] some level of shock but there were internal complaints made about his behaviour. At some level, that should’ve given an indication of potentially his attitudes and behaviour.”

“We do get indication from the complaints made against him by other officers that at least his racist views were known.”

The assault

Daniel Haile-Michael, who was only 15 at the time, was assaulted by a Victoria police officer in 2005. A year later, Guerin became the superintendent for the Flemington area, and would climb to as far as the Head of Professional Standards at Victoria police despite allegations of racist remarks.

Daniel’s assault was near the housing estates in Melbourne’s inner-city suburb, Flemington. He told me,“ We were playing basketball at our local court. It was during Ramadan [and] most people were out and about, they had just broken their fast, and yeah as usual we were just spending time walking around the neighborhood playing ball."

Daniel recalled one of his friends wanting to go to the service station for some cigarettes. “We walked from the housing estates out onto the main street where the petrol station was,” they were enjoying the walk so they thought, “let's just continue walking.”

The petrol station was not very far from the local high school, Daniel said the buildings were around “100 meters” from one another. As they walked toward the high school they noticed “security guards, or something in the school.” They felt there was trouble near so they decided to return to the estates.

Earlier that afternoon it was "muck up day," a high school tradition where students pull pranks in and around their schools in their final year. But Daniel and his friends weren’t with those students.

Suddenly, a police van appeared. Daniel remembered how it “swerved in front” of them, and “two cops came out, and they were like ‘what are you bloody idiots doing in the school?’”

Daniel explained that things got very heated, very quickly, using a very Australian expression to describe what happened next, “and it just started going off.”

The officers were alleging Daniel and his friends were throwing rocks at the school. Daniel replied to the officers saying, “we had nothing to do with it.” The answer wasn’t sufficient, and the exchange quickly became violent.

The experience went by “pretty quickly.” Daniel said he couldn't really “comprehend what was happening at the time." He’d always thought, before that moment that law enforcement was on his side. The police were supposed to protect him from violence, not inflict it on him. He described what he felt in that moment to me, “scared.”

He was in a public space, in front of the petrol station. He began “screaming,” he tells me, hoping his cries would be heard and someone might “come and help.”

Maybe somebody heard him, maybe somebody saw the violence but no one came to his rescue. He was on the asphalt beaten and bruised. His biggest fear was – what was next?

Daniel said, “if they did that in public” what would happen if “they arrest me? I was like, if I don't get away from these cops right now what's going to happen after this?” He was afraid of what was going to happen behind closed doors. Daniel told me he was “scared for [his] life.”

After the assault everything “got really real” for Daniel. He had heard stories of “friends complaining about being harassed by police officers. But [he] sort of just thought they were at the wrong place or they were doing the wrong thing. Or maybe they were just exaggerating like young boys do.” He said “when it happened to me, then it sort of felt very real.” It became tangible.

From that point on Daniel, like his peers, was on guard. He told me, “I became a lot more fearful of police and law enforcement in general.” If he saw them, was near them or anywhere in their orbit “[he] felt uncomfortable."

Daniel began to be hyper-aware of where he travelled and who he travelled with. He tells me, “I tried avoid walking alone, I always walked with friends.” He started taking a “different route to school as well. [He] tried to avoid main roads, always taking the back way.”

Daniel did all he could to “avoid those situations where, you know, [you] might be alone with law enforcement.”

In the process he felt himself losing his agency, his ability to move and travel freely in his own neighbourhood. He described it as “in some ways, you’re on a military mission. Every day you just want to get through it, survive and yeah you're just in a constant, almost a continuous state of fear."

Daniel didn’t believe sharing his experience with his parents was an option for him. He told me, “I didn’t tell them.” When I asked him why, he said, "because they wouldn't believe you, and they would suspect that you actually did something wrong.”

He described a tense and complicated relationship, how his parents’ understanding of struggle was radically different. He told me because “they are very grateful for having moved, given their refugee background, they [will] always take the side of the system.”

Daniel said if he had told them they would probably have said “just toughen up” or “this is nothing compared to what they have experienced”. So he decided to stay silent.

The case

But silence wasn’t an option for very long. The news of his assault spread in his community, eventually reaching a youth worker at a North Melbourne Youth Drop-In centre.

“They told the youth worker, and basically in one of the drop-in nights they stopped all the activities and said we needed to create a youth leadership group. To try and deal with some of these issues that are happening in the neighbourhood.”

The group of young Africans at the drop-in centre kicked into action. Daniel said they were working on a number of projects covering key issues including unemployment, lack of activities for young people and most importantly, racialised policing.

But the responsibility hit Daniel hard. He said he felt conflicted throughout the lead up to the eventual case. Daniels told me, “It was sort of tough,” he felt a constant “edge” between “what's right for [him] and what's right for the community.”

Daniel said, “the more time you spend on community issues, the less you're spending on your own personally development, and your own goals.”

“It sort of like, you felt like you kind of put your own life on pause to kind of follow this thing that needed to be done.”

It didn’t help that the case dragged on for years. Daniel told me, “I mean it wasn’t like straight ... we didn’t just straight sort of go to court.” There were negotiations between different organisations, and the process was “hard to deal with because you sort of just wanted to move on, and try and live a normal life.”

Some of Daniel’s friends, also victims of police brutality, couldn’t wait any longer, and left the case early, and he didn't blame them. He believed,“the way the justice system is set up, these processes are so arduous and long ... how much can you expect a volunteer to do and commit when you've got lawyers, police officers and all that kind of stuff who's just doing that as part of their job.”

Daniel made the point that this may have been a job for them too, but one that was unpaid. He said, “Some of us were being asked to put our lives on hold, at certain stages of it, for no individual gain.”

“For some people that was a high price to pay, for no individual reward. And given the situation that we were in like its not as if we were middle class.”

“These are people who are vulnerable, who are growing up in a housing commission, first- generation refugees who are trying to establish their life, you know, in their new homes. It was a big thing that was being asked of us in that context.”

The period between leading to the case and its conclusion took eight years. When the case was decided, Daniel was no longer that 15-year-old, self-described “nerd.” But the settlement was a bittersweet feeling tinged with relief and some regret.

Daniel said his only regret was not seeing them on the stand “explain why they did what they did.” Although, that sense of catharsis wasn’t possible for Daniel, as the officer who assaulted him had gone into retirement. He still wanted “at least for some of the other people,” to be “held to an account, no matter who [they were].”

When I asked Daniel how he felt about the current climate, how African-origin people were being spoken about, whether by politicians, senior police officers or radio shock jocks. He sighed and said, “I mean, it's unfortunate, we're sort of back where we were ten years ago or more.”

But Daniel added a caveat, “ten years ago, you wouldn’t have any politicians standing up against” comments like Dutton’s but now he said “at least there's certain section of the society who have a better understanding of what racial profiling is, and who sort of aren't afraid to call it out.”