Srinagar — Ahead of the scrapping of Article 370 that granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir, the Indian government airlifted 35,000 additional armed forces to the region to thwart any possible mass mobilisation.

Most people in Jammu and Kashmir, especially those from the Kashmir Valley, have always opposed any tinkering with the 'special status' of the erstwhile state.

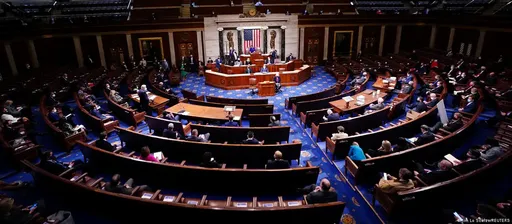

The night before India’s Home Minister Amit Shah announced the decision on the floor of parliament, a strict curfew was imposed, and a communication blackout was put in force.

However, the region, and especially the restive south Kashmir—which has seen violent protests and the highest militant recruitment in recent years—did not experience any mass protests after the central government’s move, something even Kashmiris find unusual.

So why did this happen? Well, there are several reasons.

Mohammad Akram, who hails from south Kashmir’s Kulgam district, said the restrictions imposed by the government this time were unprecedented. Had the restrictions not been in place, Akram said, there would have been violent protests against the BJP government.

“They (the central government) have brought in thousands of additional troops. The curfew is stricter than ever. There is no way people can come out to protest,” he said.

Others believe there was no mass-mobilisation because of a leadership crisis in the Kashmir Valley.

After the February 14 suicide bombing in south Kashmir’s Pulwama attack that killed at least 40 Indian armed forces, the Indian Home Ministry banned the Jamaat e Islami – a politico-religious organisation that is often credited for mobilising the masses during the 2008, 2010 and 2016 mass uprisings.

With most of its leaders, hundreds of activists and workers in jail, the street-level resistance became increasingly unlikely. The government also arrested hundreds of pro-India politicians, activists, and civil society members who had in the past played a role in leading different demonstrations against the Indian state.

“The government, this time, has taken no chances: they have put in prison all those they deem to have the potential of mobilising people or filling the vacuum left by those leaders who are already in prisons,” said a political observer from the valley who wished to remain anonymous.

Hours after the Indian Home Ministry announced to completely annex Jammu and Kashmir by repealing Article 370 of the Indian constitution–that granted Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh, autonomous status–the government arrested two former chief ministers and several former ministers. Most of the pro-Pakistan and pro-independence leaders await trial or in prison in Kashmir and India.

As such, the political observer quoted earlier said, there is no one to lead an agitation or form a strategy.

“The government has rendered people leaderless and directionless,” he said.

Pulwama, which has been home to the highest number of militants recruited, as well as militants killed, since 2014, has also not erupted.

Shakir Rasool, 28, from Pulwama’s Prichoo village said there is anger among people, but “with a strict curfew in place, it is impossible to give that anger a vent.”

Rasool said this anger would find a more violent release.

“Mark my words, it will give rise to more militant recruitment. When people are not allowed to go out of homes, not allowed to protest, where will all the anger go? It will find its way, and it will be violent,” he said.

In Pulwama’s Shadimarg village, another young man, wishing not to be quoted, said that people in his area are already under the constant watch of the armed forces. The village houses a large military camp which is meant to act as a deterrent against the organisation of protests.

“People here know that any protest against Article 370 abrogation will be met with brute force. People do not want violence. I think it is wise to be patient and not react when they (armed forces) have been given a free hand,” he said.

Others believe the Indian government’s move on Kashmir does not change much on the ground, except an attempt “to shift the goalposts.”

“It does not matter if Article 370 stays or not. Our fight was never for retaining special status. It is about the right to self-determination. We don’t believe in the Indian constitution, so it does not matter if they amend the constitution. They are just trying to change Kashmir’s narrative from a freedom movement to a demand for a 'special status',” said Suhail Bashir who lives in Pinglin in Pulwama district.

Kashmir witnessed the last mass civil agitation in 2016 when a militant commander Burhan Wani was killed in a gun battle with Indian forces in Anantnag district.

As the news of his death spread, violent protests erupted across the Valley, and the government was caught off-guard. This time around, however, the government has locked down the entire valley to pre-empt any such events.

However, a group of young boys in Kakapora believe there will be protests once the restrictions are lifted.

“As soon as they lift the curfew, people will come out on the streets. People are not going to remain silent. Revoking Article 370 is a major shock for everyone, and we are angry because it was done in secrecy. There will be consequences,” one of the young men, who identified himself as Raqib, said.

Over the past few weeks, events in Kashmir are unfolding unexpectedly. Most people are clueless about what will happen next.