Washington, DC, — The vote was supposed to reopen the US government after a record 40-day shutdown. Instead, it cracked open the Democratic Party.

Eight Democratic senators, Catherine Cortez Masto, Dick Durbin, John Fetterman, Maggie Hassan, Jacky Rosen, Tim Kaine, Angus King, and Jeanne Shaheen, crossed the aisle to join Republicans and end the shutdown.

It gave President Donald Trump a symbolic victory and set off a storm inside their own ranks.

Progressive Democrats accused them of surrender. Moderates claimed they were saving jobs. Top leadership called for calm, but the party looked anything but.

“The Democratic party’s basic problem is that it has a very narrow voting base, largely consisting of voters with university degrees and high incomes; there simply aren’t enough of these people to consistently win national elections,” David N. Gibbs, Professor of History at the University of Arizona, and an expert on US politics, told TRT World.

“It was not always like this,” Gibbs added. “Until the 1970s, the Democrats had a large working-class base, associated with a strong union movement inherited from Roosevelt’s New Deal.”

That bond began to fray when the party embraced globalisation, free trade, and financial deregulation in the 1980s. Democrats started speaking the language of markets rather than factories, of climate goals rather than coal mines.

“After 1980,” Gibbs said, “the party moved toward free market policies that were harmful to working people, combined with an elitist style of communication around issues of gender, race, and sexuality that lacked broad appeal.”

The result is a party that no longer shares a common language. On one side, progressives such as Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Pramila Jayapal insist that the only way to confront Trumpism is through moral clarity and class politics. They see compromise as cowardice.

On the other hand, senators like Joe Manchin and John Fetterman preach pragmatism, warning that confrontation scares off the swing voters they need to win.

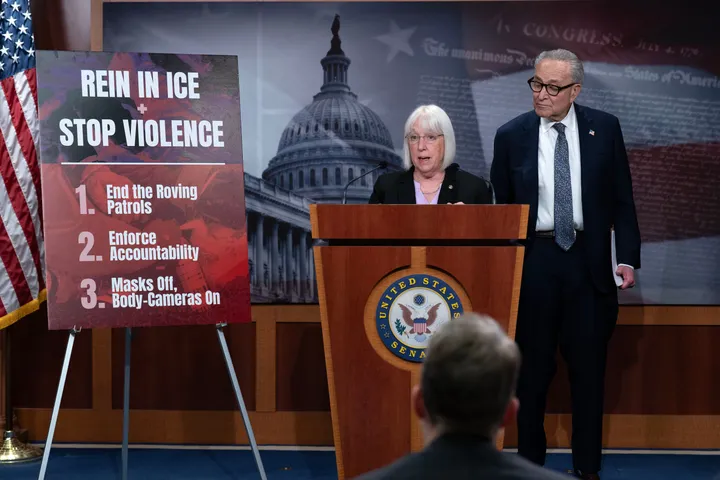

Between the two, leaders like Chuck Schumer and Hakeem Jeffries juggle impossible expectations, trying to keep a party together that doesn’t want the same things anymore.

The Senate shutdown vote exposed that fracture in full view. Progressives erupted on social media, calling the deal a “giveaway to Trump.”

Democrat Ritchie Torres said it was an “unconditional surrender that abandons 24 million Americans who are about to see their (health) premiums more than double.”

Zohran Mamdani, New York City’s incoming Democratic mayor, said the deal and those backing it “should be rejected.”

Identity crisis disguised as strategy

Thirty-three Senate seats will be contested in the midterms next year, and Democrats are fighting to defend or capture them.

As word of the shutdown deal spread, several candidates for open seats — Graham Platner in Maine, Mallory McMorrow in Michigan, and Zach Wahls and Nathan Sage in Iowa — repeated their criticism of Chuck Schumer’s leadership.

As Senate Minority Leader, Schumer opposed the bill, arguing that it failed to protect health care access, but also failed to silence critics within his own party.

“Chuck Schumer failed in his job yet again,” Platner said in a video on X. “We need to elect leaders who want to fight.”

The moderates pushed back, saying real governance required compromise, not theatre. Fetterman defended his vote, saying, "It's always been wrong for us to shut the government down."

Senator Jeanne Shaheen elaborated. “What happened over the last 40 days is we crystallised the fight about health care for the American people and made it clear who’s holding that up,” Shaheen, a former governor, said in a statement.

“It’s President Donald Trump, it’s Speaker Johnson, and it’s the Republicans who have been unwilling to do anything to address the rising costs of health care,” Shaheen said.

To Gibbs, the Democratic defence reveals something deeper — an identity crisis disguised as strategy. “As unpopular as Trump is, the Democrats are even less popular,” he said.

“The Democrats elicit relatively little support among working-class voters, who increasingly vote Republican.”

Many see a political elite fluent in the language of inclusion but distant from economic pain.

Trump’s message, by contrast, is emotional, not technocratic. The Democrats, caught between moral posture and pragmatic survival, sound divided even when they agree.

“Many in the party recognise the problem and are trying to broaden its electoral base,” Gibbs said.

“Heavy lift for Democrats”

Others think that Democrats will overcome this round of infighting.

“The infighting over the deal will fade quickly and by the time we get closer to the midterms, it’s very clear that Democrats will aggressively prosecute the case against Republicans on health care,” Matt Bennett, co-founder of the Washington, DC, based think tank Third Way, said in an interview.

A recent Newsweek map shows Democrats closing the gap with Republicans in the national redistricting battle ahead of the 2026 midterm elections.

According to the Economist, they have a good chance of retaking the House of Representatives in November next year. That would end the legislative phase of Trump’s presidency and usher in a period of oversight hearings.

House Minority Leader Jeffries said he is confident Democrats will take back the House in the 2026 midterm elections and is optimistic about his party’s chances to win back control of the Senate.

As the party looks ahead to reclaiming power, internal divisions continue to surface.

The eight senators who crossed the aisle may have paved the way to reopen the government, but they also reopened an old wound.

As Gibbs put it, “It will be a heavy lift for the Democrats to recast their image.” The real question is whether they still know what they’re lifting for.