Almost immediately after two American MQ-9 Reaper drones killed Iran’s most senior military leader, Qassem Soleimani, the social media erupted with speculation over whether this marked the opening shots of an all-out war.

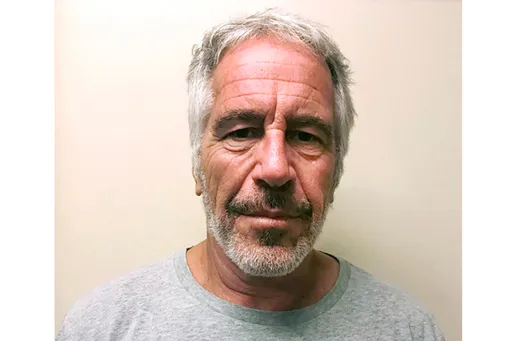

Major General Qassem Soleimani was more than just military leader of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp’s elite Quds unit or de-facto head of intelligence. He also masterminded Iran’s regional security strategy that allowed Tehran to manage militias and paramilitaries throughout the region with relatively small footprints, moving it up into an altogether class.

In some senses, his killing could be construed as an act of war, if outrage in Congress on Trump’s failure to request authorization for the strike is anything to go by.

Many argue it already has. The US War Powers Resolution requires the US president to notify Congress within 48 hours of committing armed forces to military action, or declaring war. He didn’t.

Legal definitions notwithstanding, Soleimani’s killing is in an entirely different category from the tit-for-tat escalations that have marked Iran-US tensions over the years.

But where will it all lead?

Here are the top 5 questions on the risks of a US-Iran war answered.

1) Does Soleimani’s death increase the possibility of war?

Most analysts believe that Qassem Soleimani’s death can only force Iran to retaliate. This isn’t necessarily for ideological reasons. It’s an act of self-preservation and deterrence that most countries will follow, and entirely different from strikes on militias or equipment. The death of a major figure like Soleimani strikes at Iran’s ability to operate in the region. Iran may feel forced to escalate or retaliate just to prove that the killing of its leaders causes reactions so severe, the US should think twice before doing it again.

The level of retaliation is nearly impossible to know ahead of time, but it can be identified along a range. If acting in their self-interest, Iran has to send a message of deterrence that would convince the US that Soleimani’s death was outweighed by the costs. At the same time, they can’t retaliate too strongly or risk provoking all-out warfare.

Achieving this balance is difficult, given Soleimani’s high-value as a target, but even then, any escalation can be miscalculated, perceived differently or cause a chain-reaction of events that can only lead to war.

This is already taking place. The events that lead to Soleimani’s death were a result of reactions that only forced the other side to escalate further, instead of backing down.

This is already brewing into a dangerous cycle. After all, did anyone expect the shelling of an Iranian militia camp, the killing of a US contractor, the storming of the American embassy in Baghdad, or the death of Soleimani?

2) Can out-of-control escalation happen?

Escalation is difficult to control on a sunny day. But to make matters more complex, US aims and statements don’t always match. While the US state department describes limited targets of deterring Iran, Trump often speaks of much more drastic actions like toppling the Iranian government, or bringing their economy to a halt.

With the size of the US military, this is likely not taken with a grain of salt by Iranian leadership. Instead, it forces them to plan for the worst, making it harder to back down from escalation if only to maintain deterrence.

When severely challenged, nation states have two choices. Negotiate a deal or use force to push back. The best case of this is Iran’s agreement to the 2015 JCPOA nuclear agreement to reduce US sanctions. This was only possible when the US made the effort of showing Iranian leaders that the terms were to their benefit, were supported by the international community, and didn’t risk their security. It took months of negotiations to reach this point.

With a US President known for sudden decisions, and pulling out of agreements, Iran’s strategic calculus can’t count on stability and his interest in peace. In this case, escalation and counter-attacks may seem like the better option.

3) What could Iran’s counter-attack look like?

Iran is ranked as a highly militarily capable country than any the US has fought since WWII, including Iraq or even North Vietnam. It has spent a long time preparing for a possible war given its geopolitical circumstances.

Iran will likely respond asymmetrically, through the use of proxy war or small groups that can target American troops, their allies or its economic concerns.

Historically however, asymmetrical warfare has never caused the US to de-escalate, even if it has worn out public opinion over drawn-out wars. On the flip side, the US has never been able to figure out a compelling playbook for preventing or defending against asymmetric strategies short of using overwhelming force.

There’s a deep risk to Iran’s use of asymmetrical warfare. One asymmetric response may not trigger a war, but low-intensity asymmetric conflict is still conflict, and can easily snowball into high-intensity conventional war. Both sides could find themselves in a war without remembering what triggered it.

Iran is unlikely to win a full-on conventional war with the US, but at the same time the US can’t reliably occupy or conquer Iran without paying the price of a difficult and costly ground war. Iran also has a significant missile arsenal that could cause significant damage to US bases and allied countries in the immediate region.

4) Would a US-Iran conflict spread?

While Iran can muster proxy militias in Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen and Syria, few actual governments would be willing to risk a full-on war with the US. Even US allies like Israel and Saudi Arabia would be hesitant to directly participate unless they were the victim of Iranian attacks.

Given the cost of war, the US and Iran are more likely to avoid it. This isn’t just the toll in human lives such a conflict would bring. Brown University’s Costs of War project found that the US’s post-9/11 wars have cost at least $5.9 trillion. Analysts suggest that a full-scale war with Iran could cost trillions amid rising budget deficits, failing infrastructure and needed reforms to education, health care and economic growth.

But there’s also the global economic context to look at. A war with Iran would target oil facilities, shutting off resources the world relies on. Even with US 2018 sanctions, Iran produces a reduced 2 million barrels of oil per day, and exports nearly half a million of them worldwide.

A war in the Persian Gulf would profoundly destabilize the global oil system. If the Trump administration strikes Iran, unilaterally or in conjunction with Saudi Arabia, and targets the state’s oil facilities, these attacks will take more resources offline. Although Iran’s oil output has declined significantly since the United States reimposed sanctions in 2018, the country still produces more than 2 million barrels of oil per day and exports about half a million barrels per day of petroleum products and liquefied petroleum gas to a variety of resource consumers. This could cause a global energy crisis or severely impact markets, with a limit to how long national strategic reserves can put off national discomfort and rising prices.

While the risks of an unintended creep to war are difficult to dismiss, fears of WWIII are largely exaggerated. While other countries such as Russia and China may oppose any US attacks, they’re highly unlikely to join the fight themselves in the same way they didn’t join other US wars.

5) What about Iran’s nuclear agenda?

Iran announced Sunday that it would no longer be bound by any limits of the 2015 JCPOA nuclear deal that prevented it from enriching weapons grade uranium.

Iran is also influenced by its geography. While it may play the role of a regional power-player, it’s still more or less encircled by Sunni Gulf States and US allies on every side.

For nearly 40 years, however, Iran has avoided direct conflict as it sought to enhance its standing and ability to project force through the region by asymmetric means. The only effective way for Iran to truly become a regional hegemon is if it can has the strongest deterrent: nuclear war.

The weeks and months ahead will show whether Iranian leadership find the benefits of pursuing nuclearization outweigh the risks, or if the issue of enrichment is better used as a negotiating tactic.