Allegations that Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein demanded sex from women and raped some who refused his crude advances continue to have far-reaching repercussions. But what of a powerful man whose ambitions were not derailed by similar charges?

Nearly a year ago, Americans elected Donald Trump president despite a number of women coming forward during the campaign to say he had sexually harassed or assaulted them, and despite the release during the election campaign of a 2005 videotape in which he bragged about kissing, groping and sexually pursuing women with no regard for whether they gave consent.

The full impact of the allegations against Trump may only be clear years from now.

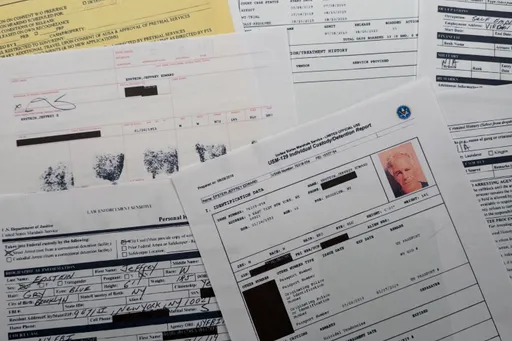

Few of the women who have accused Trump have taken legal action, which as the Weinstein and other cases have shown is not unusual, often because women have seen others shamed and blamed in such circumstances. Trump has portrayed his accusers as liars. He apologised for and downplayed his comments in the video made while the “Access Hollywood” show was taping a segment about him. Trump could be heard saying in the video that he felt he had license when it came to women he found attractive to “grab them by the pussy.”

Women in pink “pussy” hats were among the hundreds of thousands who gathered in Washington and across the country for post-inaugural, anti-Trump protests. Those kitten-eared hats symbolised a new willingness to speak out about sexual misconduct in general and a determination that Trump be held to account, Lorraine Bayard de Volo, an associate professor of women and gender studies at the University of Colorado, told TRT World.

EMILY’s List, founded in 1985 to encourage pro-choice women Democratic Party candidates and fund their campaigns, has featured those pink hats in campaigns to encourage women to run for office. The organisation says more than 20,000 women have signed up to run for office since Trump’s election.

“We’re two steps forward even though that was a big step back,” Bayard de Volo said of Trump’s election.

On the eve of the anniversary of the release of the “Access Hollywood” Trump videotape, a relatively new women’s advocacy group known as UltraViolet arranged for the tape to be played on a continuous loop for 12 hours on a screen set up behind the White House. A day earlier, The New York Times had broken the Weinstein story.

“Trump’s election has inspired a new call to arms in the fight for gender equality, and these last nine months have underscored the urgency for all of us to work in coalitions with racial justice groups, immigrants' rights organisations, and others to build an active resistance to Trump and his administration,” Nita Chaudhary and Shaunna Thomas, cofounders of UltraViolet, wrote in a TeenVogue op-ed last month, speaking to a new generation of activists. “People's lives and safety are at risk. But together, we will resist. And together, we will win.”

Previous watersheds can be instructive. EMILY's List was among organisations that tapped into the outrage many women felt in 1991, when Clarence Thomas was nominated for the US Supreme Court. Law professor Anita Hill accused Thomas of sexually harassing her when he was her boss at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency charged with ensuring Americans don’t face discrimination at work. Members of the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee sharply questioned Hill’s behaviour and credibility in a very public illustration of why women so often keep quiet when they have been harassed or assaulted.

Anger over Hill’s treatment turned into donations and votes. The following year, 1992, was dubbed the “Year of the Woman;” elections saw the number of women in the senate tripled to six. This year, the United States has 21 women in the 100-member Senate; three of the women sit on the Judiciary Committee.

Beth McCann, who heads the prosecutor’s office in Denver, Colorado told TRT World it was encouraging to see so many women using tools like the #MeToo social media campaign to speak out about their own experiences of harassment and abuse. But “it’s just depressing that it’s still going on to the extent that it is among people that you think would know better.

“It’s hard to understand.”

Challenging victim-blaming

McCann hopes that women who have found strength by sharing their stories on social media will take the next step and file criminal charges or open civil suits in such cases. A lawyer since the 1970s who says she has been inspired by Hill’s and others cases to be passionate about defending victims of sexual assault, McCann said she has seen other prosecutors taking the issue more seriously in recent years. But she acknowledges female accusers who go to court still have to face questions about their own behaviour. In most such cases, the only witnesses are the accuser and the accused, and jurors must decide who is more credible.

“There is still so much victim-blaming in our society that it’s frustrating,” McCann said.

But she said attitudes are changing and will continue to change as more and more women enter the workforce and rise to powerful positions in many fields. McCann became the first woman district attorney in Denver’s history after winning an election in 2016 in which her opponent was also a woman.

Earlier this year, McCann took to the op-ed pages of her local newspaper to draw attention to what she saw as the courage of megastar Taylor Swift. Swift had been dragged into court by an obscure radio host who alleged she had ruined his career by accusing him of groping her during a pre-concert meeting with fans in Denver in 2013.

Swift could have settled, the legal equivalent of what many women have done and what Hill told the senators she would rather have done: keep quiet and move on. Instead, Swift counter-sued and won a court decision that she had done no wrong by disclosing an assault to her mother, who ensured Mueller’s employers were informed. A civil jury also found that radio host David Mueller had assaulted and battered Swift and awarded her the symbolic $1 in damages she had requested. Swift said she wanted to make a point, not ruin Mueller financially, and she pledged to support groups that help victims of sexual assault defend themselves.

On the stand, Swift looked at Mueller as his lawyer subjected her to a barrage of questions reminiscent of Hill’s exchanges with the senators. Swift was asked what she could have done differently before, during and after the attack. She was forthright that the issue was not her behaviour, “Your client could have taken a normal photo with me.”

McCann said Swift showed young women that “even a super star can be sexually assaulted and will stand up for themselves”.

The Swift trial was closely followed by the star’s young fans. Her fan base, along with other women more generally, may have found Mueller more recognisable than a Weinstein – Mueller was the kind of man they might actually meet and have to endure in their own workplaces.

Hotel workers suffering routine harassment by guests

Last year, a local chapter of UNITE HERE, a union that represents hospitality and other industry workers in the US and Canada, released the results of a survey of 487 women asked about gender-based harassment and violence on the job in Chicago-area hotels and casinos.

Nearly six out of every 10 hotel workers and eight out of 10 casino workers who responded reported sexual harassment at the hands of a guest. Half the housekeepers reported having had a guest answer the door naked, expose himself or flash them. Two-thirds of the women had never reported their harassment. Among those that did, most said they had seen nothing change after others made reports. Even more chilling, others said such treatment from guests was so common they no longer reacted.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, for which Hill and Thomas once worked, received between 6,000 and 8,000 complaints of sexual harassment on the job – the vast majority from women – in each of the years between 2010 and 2015. The Commission believes the actual incidence is much higher because the majority of victims don’t come forward.

Unions pushed for a proposal signed into law in California earlier this year that will, as of 2019, require companies that provide industrial cleaning services to ensure supervisors and janitors get training to combat sexual harassment and abuse. The legislation is an example of the kinds of steps that can follow when awareness is raised and organisations tap into reaction that can be amplified by social media campaigns.

Women and gender studies expert Bayard de Volo said a broad movement could result from the new attitudes evident in the response to the Weinstein allegations. She said that would include marches and political campaigns, but also momentum that will give more women decision-making roles in the arts and business.

“It’s been called sometimes the Harvey Weinstein ripple effect,” she said. “I think the ripple began before that. It’s hard to identify … what the first stone thrown was.”

Bayard de Volo was struck by her undergrads’ reaction recently when she showed them video of Hill appearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee. She said students who recoiled at the tone and perspective of the questions Hill faced “felt that we had already come a long way.”