Uber is driving right into a legal roadblock over its alleged use of computer algorithms to decide the fate of its drivers.

On Monday, the UK-based App Drivers and Couriers Union (ADCU) filed a lawsuit in the Netherlands, where the ride-hailing giant's headquarters is located along with its massive database.

Four drivers from the United Kingdom and Portugal say they were blocked out of the app without the company telling them what exactly they had done wrong.

The lawsuit is the first of its kind that has been filed under the General Data Protection Regulation’s (GDPR) Article 22.

GDPR, introduced by the European Union in 2018, protects user data and allows European citizens to demand information if they feel an automated decision was made about them.

“In each of the cases the drivers were dismissed after Uber said its systems had detected fraudulent activity on the part of the individuals concerned. The drivers absolutely deny that they were in any way engaged in fraud and Uber has never made any such complaint to the police,” the ADCU said in a press release.

Uber’s algorithm decides which driver or courier gets the job, giving the company significant leverage when it comes to deciding who makes more money.

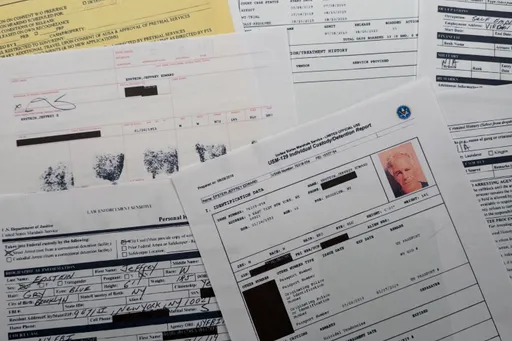

The case is basically about how Uber treats its drivers. For the company, all the drivers are self-employed contractors - not bound by management control. That’s also another way of saying that the drivers are not its employees and consequently they don’t have the usual employee rights.

If the drivers do not qualify as Uber employees, then how can it ‘fire’ the drivers based on performance-related metrics, the union says.

“Uber has never given the drivers access to any of the purported evidence against them nor allowed them the opportunity to challenge or appeal the decision to terminate,” ADCU said.

It has long been known that Uber is on the lookout for drivers who try to skirt its system. Tactics such as deliberately trying to increase the duration of a trip, and provoking customers to cancel rides, are listed as frauds on the company’s website.

James Farrar, who lobbies for rights of workers in the digital economy, says that Uber was penalising its drivers for trying to make an extra buck by declining rides.

“Uber, not ironically, calls such behaviour ‘gaming the surge’. Apparently, only Uber is allowed to ‘game the surge’,” he told Sifted.

Such an approach where the tech giant is effectively controlling the drivers, undermines one of the fundamental parts of the gig economy: that workers can work whenever they want.

Despite being self-employed, Uber drivers have little control over their jobs. Their routine depends on an app that does not tell them anything about the next ride. If a driver decides to skip a few rides, he’s blocked by the app.

Uber’s motto is that drivers are in the driving seat with little interference from the management. But it rates driver profiles on matters such as inappropriate behaviour and late arrivals.

One driver, whose contract was terminated, told the BBC that he contacted Uber 50 times over a year but wasn’t given any reason for his termination.

On its part, Uber says the accounts of the drivers were deactivated after manual reviews.

The case has become a test case for checking the power of internet-based companies, which use data to decide the fate of thousands of people.

Uber has 3.9 million drivers worldwide and tens of millions of people take rides using its app every month, making it an important part of the gig economy. People across the world use the app to work full-time jobs.

Article 22 is a check on the use of powerful algorithms as it allows people to see how their information is processed.

Uber is already facing a legal challenge by drivers who say they should be treated, as company employees entitled to minimum wage and public holidays instead of self-employed contractors.